Thomas “Tom” C. Church Named 2018 Citizen of the Year

Tom C. Church, dedicated supporter of local education, founder of the Henderson Community Foundation and local businessman, was named Citizen of the Year at the 81st annual Henderson-Vance County Chamber of Commerce Banquet held in the Civic Center of Vance-Granville Community College on January 31.

Tommy Hester, the 2017 Citizen of the Year recipient, presented the prestigious award, which honors an individual who has made a positive impact for the betterment of the community through personal involvement and contribution of volunteer time and efforts.

“The Citizen of the Year Award is very special. The honor is earned by an individual who has made a significant contribution and demonstrated a commitment to the advancement of Henderson and Vance County,” said Hester.

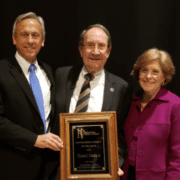

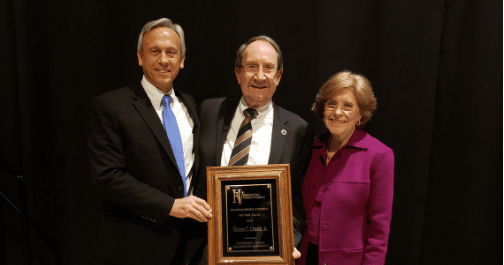

Left to right: John Barnes, president of the Henderson-Vance County Chamber of Commerce, 2018 Citizen of the Year recipient Tom C. Church and wife Gillie Church.

Each year, an anonymous committee selects the honored citizen, with the name of the recipient being a closely guarded secret until announced at the annual chamber banquet.

Prior to announcing the name of the 2018 recipient, Hester gave a brief background of Church’s life and service to his community. “Portrayed as a guiding light to what community service is all about, our 2018 Citizen of the Year is constantly involved in promoting Henderson and Vance County. Graciously and humbly committed to Vance County with a passion for volunteerism and charitable giving, our recipient avoids attention and shuns the glare of publicity, which led one admirer to describe our Citizen of the Year as an unsung and unpretentious star of Vance County.”

Hester continued by listing several of Church’s numerous community achievements including:

- Treasurer and original board member of Henderson Collegiate Charter School

- Lifetime trustee of the Kerr-Vance Academy Board

- Board of Trustee member for Maria Parham Health

- 2018 Chairman of the Maria Parham Health Joint Venture Board

- Board of Trustee member for Occoneechee Council of the Boy Scouts of America

- Personal contributor to McGregor Hall Performing Arts Center

- Past chairman of the Henderson-Vance County Economic Development Commission

- Member of the charter team that conceived and built the Henderson Family YMCA

- Previous Senior Warden of Henderson’s Holy Innocents Episcopal Church

- Member and past president of the Henderson Rotary Club

Born and raised in Gastonia, NC, Church is a graduate of Ashley High School and North Carolina State University where he received his degree in Civil Engineering.

Hester said that upon graduating from NCSU, Church was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the US Air Force, serving for six years as a fighter pilot and logging over 400 combat hours during the Vietnam War.

In addition to being a two-time recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross during his time in the military, Church also received the Bronze Star and nine Air Medals for valiant service.

Upon leaving active duty Tom and his family settled in Henderson where he co-founded Ashland Construction Company, a multi-state commercial construction company, and co-founded Plantation Realty Company, a commercial real estate firm.

Church is married to Virgilia (Gillie) Leggett Church and they have a daughter, Gillie Nichols, of Manteo, NC, a son, John, of Raleigh, NC and two granddaughters, Lucy and Anna.

Hester concluded his speech by simply stating, “Tom Church, our 2018 Citizen of the Year, what an asset for Vance County.”

Church then took the stage with his family and said he was at a loss for words. “What do I say? I’m humbled, honored and shocked; you caught me off-guard.”

Thanking his wife, family and business partner for their encouragement and support, Church told the crowd that he and his family deeply love their community. “Henderson has been good to me and my family. We love Henderson and it has loved us.”

Proving his humble nature that was alluded to several times in Hester’s speech, Church concluded by saying, “If I’ve been able to do anything to give back to this community for what it has given me, I am very honored and proud.”