Nowadays, health professionals are quick to point out the importance of staying hydrated and drinking enough plain ol’ water as a key component of good health. A good rule of thumb is eight 8-ounce servings of water each day.

But around the time of the Civil War to the turn of the 20th century, there were a number of mineral springs in the area whose proprietors made great claims about their water’s restorative properties.

There was sort of a mineral springs “belt” that was loosely situated across Halifax County that ran through Warren and Vance counties on the way toward the Clarksville area, according to Mark Pace, local historian and N.C. Room specialist at the Richard Thornton Library in Oxford. Pace joined WIZS’s Bill Harris on the tri-weekly history segment of TownTalk Thursday and talked about the heyday of the area’s mineral springs and the visitors who came in search of health restored.

The waters of Panacea Springs in Littleton, for example, was reportedly good for whatever ailed you – from excema to digestive problems and everything in between.

Shocco Springs in Warren County and Buckhorn Springs in northern Granville County joined other mineral springs that developed national reputations – not just for their water’s restorative powers, but as vacation destinations for the rich and famous of the time.

Marketing played a key role in the popularity of the springs, Pace said, but it was the railroad that played a major role.

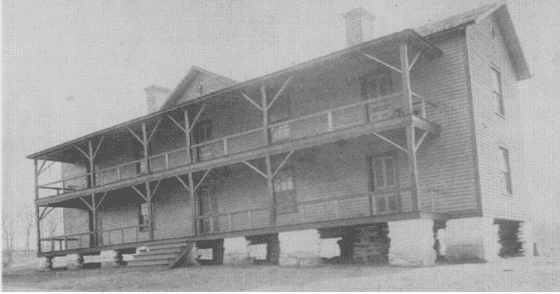

“Kittrell wouldn’t even exist if the railroad hadn’t come through,” Pace said. The medicinal benefits of the waters aside, hotels sprang up around some of them to accommodate the travelers. There were four hotels in Kittrell, for example. Kittrell Springs Hotel had a bowling alley, miniature golf, concerts and horseback riding just to name a few amenities.

Back in 1858, “you didn’t go to Nags Head, you went to a place like this,” Pace remarked.

The Panacea Springs resort in Littleton hosted Renaissance festivals back in the years leading up to the Civil War; Jones Sulphur Springs in Warren County included among its guests Annie Lee, daughter of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. She was sent there to ease the effects of tuberculosis and died there in 1862.

There aren’t many structures left on the sites of the old springs, Pace said – some stone foundations and a small bottling building here are a couple of remnants.

The Buffalo Springs near Clarksville remains active, and visitors can see where the famous water erupts from the ground.

It used to be called Buffalo Lithia Springs because of the claims that the water contained contained lithium bicarbonate.

But when Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, the Buffalo Lithia Springs claims were called into question. When the water was tested in 1910, Pace said, but the news wasn’t good: Although the water was shown to have traces of lithium, a person would have to drink hundreds of thousands of GALLONS of water a day to reap the benefits. Needless to say, the springs operation lost the Supreme Court case and had to change its name to Buffalo Springs.

They sold bottled water from there until 1941, Pace said, making it one of the last mineral springs operations in the area.

It also was a stop on the vaudeville circuit and one of the seasonal performers was a very talented Mr. Ebsen from Florida, Pace recounted. Eventually, Ebsen’s son, Frank, got his start at Buffalo Lithia Springs, Pace said.

He became better known as the performer and actor Buddy Ebsen.